A Chess-AI is something of a rite of passage for every software engineer, as is a snake clone or a calculator console application. If you did not try to build one yet, you are certainly missing out (or preserving your own sanity, whatever you prefer). Between the chessprogrammingwiki.org and other online resources this is now a pretty well explored field, but that is not to say that innovation is impossible and nothing changed since the days of Deep Blue (the first ever chess computer to officially beat a grandmaster).

In recent years Stockfish, the most advanced computer chess engine, has gotten a major upgrade in the form of a NNUE, a fast neural network of sorts which is used as it’s evaluation function, instead of the previous rule-based approach. The replacement of the hand-crafted evaluation function by a neural network seems to be just one more example of the Bitter Lesson.

An evaluation function does exactly what it sounds like, it is used by the engine to evaluate the current position. This is essential for the computer, in order to know what moves are better than others. The better an engine’s evaluation function, the better it is (in theory).

Today I would group chess engines into two categories: “explore the most possibilities as fast as possible” (Stockfish, using a fast evaluation function) and “have a very sophisticated evaluation function in the form of a neural network” (Leela Chess Zero, using a slow evaluation function).

What is left for amateurs, such as myself then?

Sebastian Lague has the perfect answer to that question: a competition that imposes an arbitrary limit on the length of your bot’s code. To be exact, every participant has a maximum of 1024 tokens at his disposal to craft the best chess player they can.

Sounds like a lot, or extremely little depending on your conception of tokens. In this case, a token is the smallest unit the C# compiler can see, with some exceptions. Therefore your 28 character Java-style variable ChessEngineBotThinkingBoardGamePiecePlayerMoverFactory will only count as a single token, while { also counts as one.

Further limitations are imposed on loading external files or using certain functions to extract variable names, to prevent skirting the rules. These are enforced by limiting the allowed namespaces.

Trying to improve the evaluation function

This limitation prevents the implementation of any neural networks or complex evaluation functions necessary for chess engines of the second type described above. This naturally would lead participants to choose to implement an efficient algorithm to search as much of the game tree as possible.

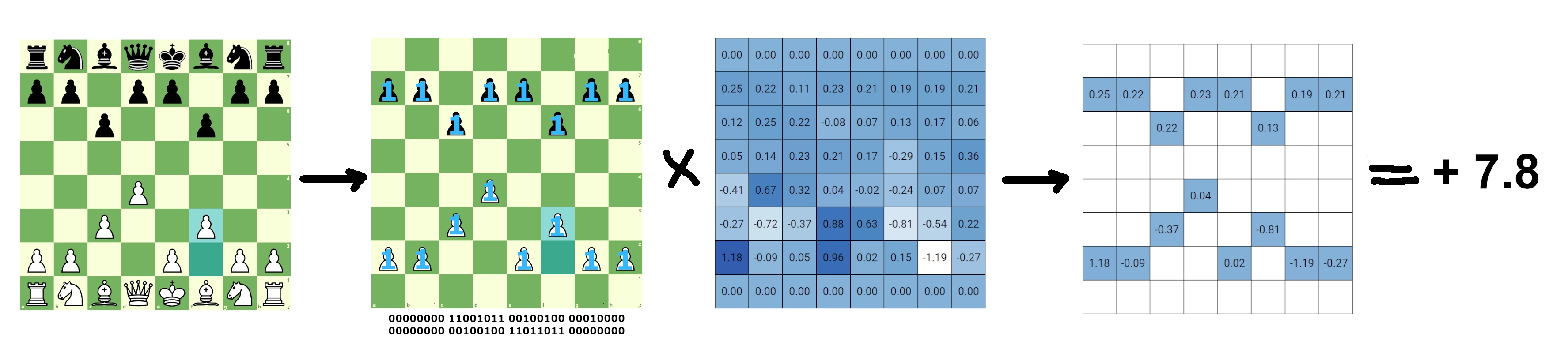

Despite this, instead of optimising for a rule-based, handcrafted approach, I wanted to do something akin to knowledge distillation. It would be inspired by the NNUE of Stockfish, that uses the current board as the input and applies the weights and biases of the model to come up with a number.

If, instead of using a complex network, we used a single 8x8 grid of weights for each type of piece, trained on already evaluated positions, I hoped to distill the game knowledge of powerful engines into a very small number of bytes. This evaluation function could then still be “plug and play” with a traditional Minimax engine and give our bot a crucial competitive advantage, while still staying inside the allowed 1024 tokens.

To anyone familiar with chess engine programming, this is essentially the concept of a PST, a piece square table. What’s new with my approach is the way it’s values will be fine-tuned.

The Idea

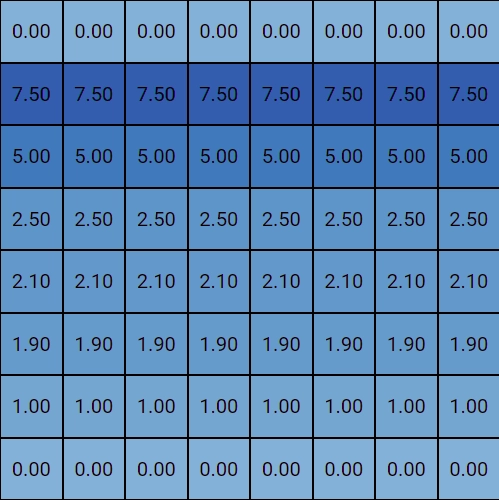

A very basic approach for creating an evaluation function is adding up the values of each piece a player has on the board and calculating the difference between these values for both players, which results in a score. Instead of assigning a static value to each type of piece (8 for a queen, 3 for a knight etc…) we weight their value based on their position on the field. One basic improvement we could make is to increase the value of a pawn the further it progresses up the board.

Instead of coming up with such rules by ourselves, copying the idea of the NNUE, we “train” our model on a lot of games and come up with very sophisticated weighting strategies.

The implementation would work as follows. Store the weights of each square in a seperate array for each piece. To evaluate, we take a bitboard (1 means a piece is present on the square, 0 indicates that no piece is there) representing the different pieces on the board as an array, and multiply it and the model’s weights together.

The result would be a board with only the values of the currently occupied squares left. We then take the sum of the values of the 6 different boards (6 piece types: pawn, knight, bishop, rook, queen, king) for each player. By then substracting both of these sums - which represent each player’s strenght - we get a value in the format of the classic stockfish evaluation. -1.5 for example to represent black winning by a small margin, +7.9 to represent white having a very powerful advantage.

Implementing the genetic algorithm and training

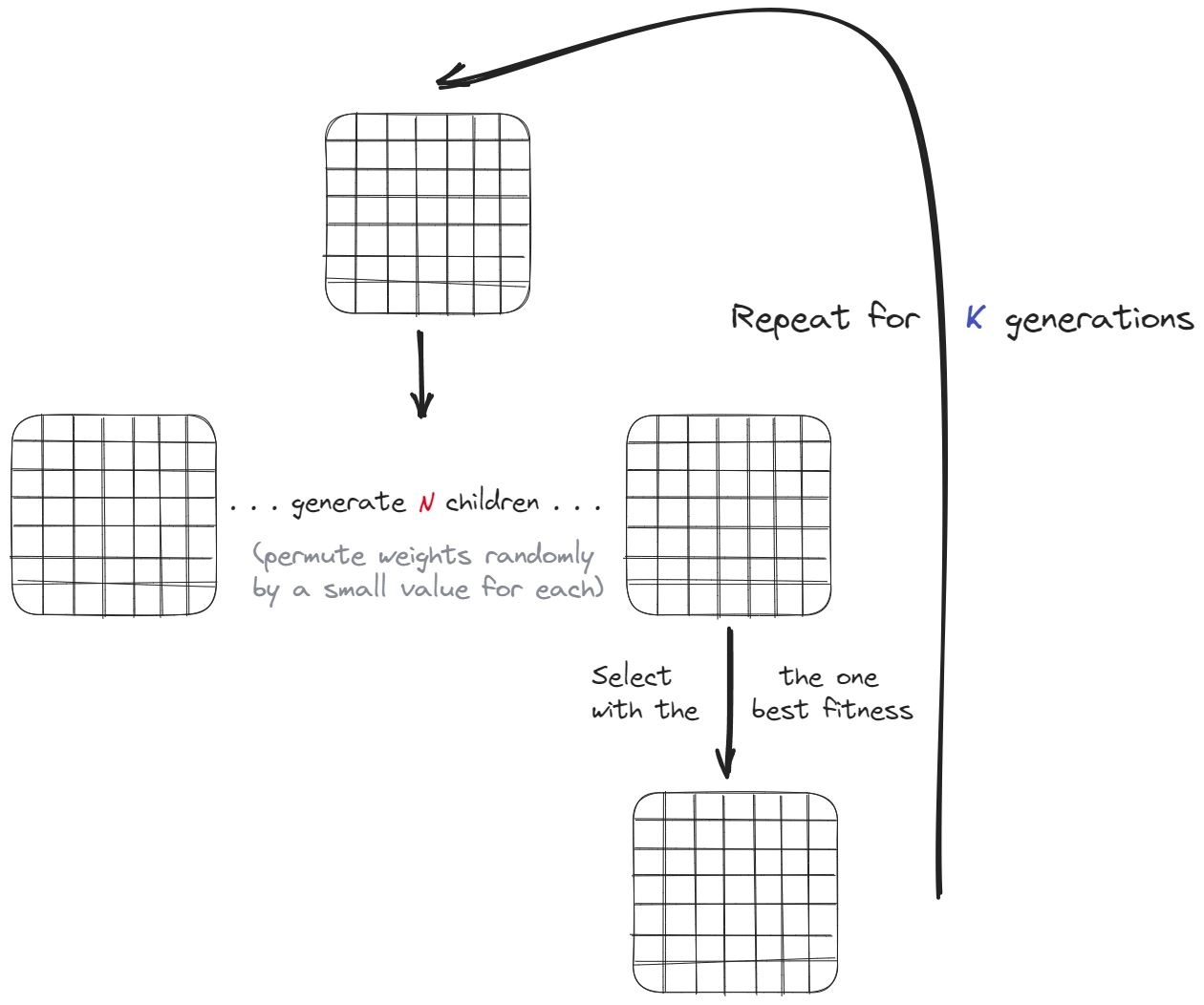

How do we “train” our model?. A tried and tested technique of machine learning seemed perfect: genetic algorithms. The issue with other traditional techniques, such as back-propagation, is that there is simply not the space to have additional neurons with weights and biases. Remember, we need to keep our bot’s entire code under 1024 tokens.

Genetic algorithms on the contrary don’t use these more sophisticated techniques, and just mutate the values of the boards randomly between generations, always selecting the best of the current generation.

Our training would therefore look something like this: we instantiate the model with randomly selected numbers between some reasonable boundaries. We then evaluate these “weights” on known chess-board positions to assign a fitness to each. At the end of each iteration, we select the very best. We then slightly and randomly mutate the values to create a lot of “children” of the best model and test their fitness again. This is the genetic (or evolutionary) part of the algorithm.

Rinse and repeat for a few hundred generations and we would be left with a single model that has been optimized for the fitness function.

Fitness function

But we still need to define an appropriate fitness function. We want to chose the models that have the best chance of producing accurate evaluations for a wide variety of positions. To do this I downloaded a large number of lichess games in PGN format. PGN stands for “portable game notation” and it encodes chess games into a series of moves with a bit of metadata.

[Event "F/S Return Match"]

...

[White "Fischer, Robert J."]

[Black "Spassky, Boris V."]

[Result "1/2-1/2"]

1. e4 { [%eval 0.17] [%clk 0:00:30] } 1... c5 { [%eval 0.19] [%clk 0:00:30] }

2. Nf3 { [%eval 0.25] [%clk 0:00:29] } 2... Nc6 { [%eval 0.33] [%clk 0:00:30] }

[...]

13. b3 $4 { [%eval -4.14] [%clk 0:00:02] } 13... Nf4 $2 { [%eval -2.73] [%clk 0:00:21] } 0-1

I then extracted the evaluation for each position and stored these for training, resulting in a few hundred thousand lines of chess positions, each with an accurate (mostly Stockfish-based) evaluation.

This seemingly random string is actually a FEN string, which stores the position of each chess pieces. It encodes a chess board into a single easily stored string. Paired with the evaluation of a powerful chess engine, this is the perfect dataset to train my own engine.

{

"positions": [

{

"fen": "rnbqkbnr/pp1ppppp/8/2p5/4P3/8/PPPP1PPP/RNBQKBNR w KQkq - 0 2",

"eval": 0.19

}

]

}

Finally, the fitness function would consist of evaluating a position from this dataset with each of our mutated models. To get the best child in a generation we would then take the one with the lowest difference from the actual evaluation.

Disappointing results

My enthusiasm for this idea quickly ebbed away once I realized how long training would take to converge to useful results and also how bad the first dozen generations really were. Plugging in the values of the best models produced mediocre results, even against very weak opponents.

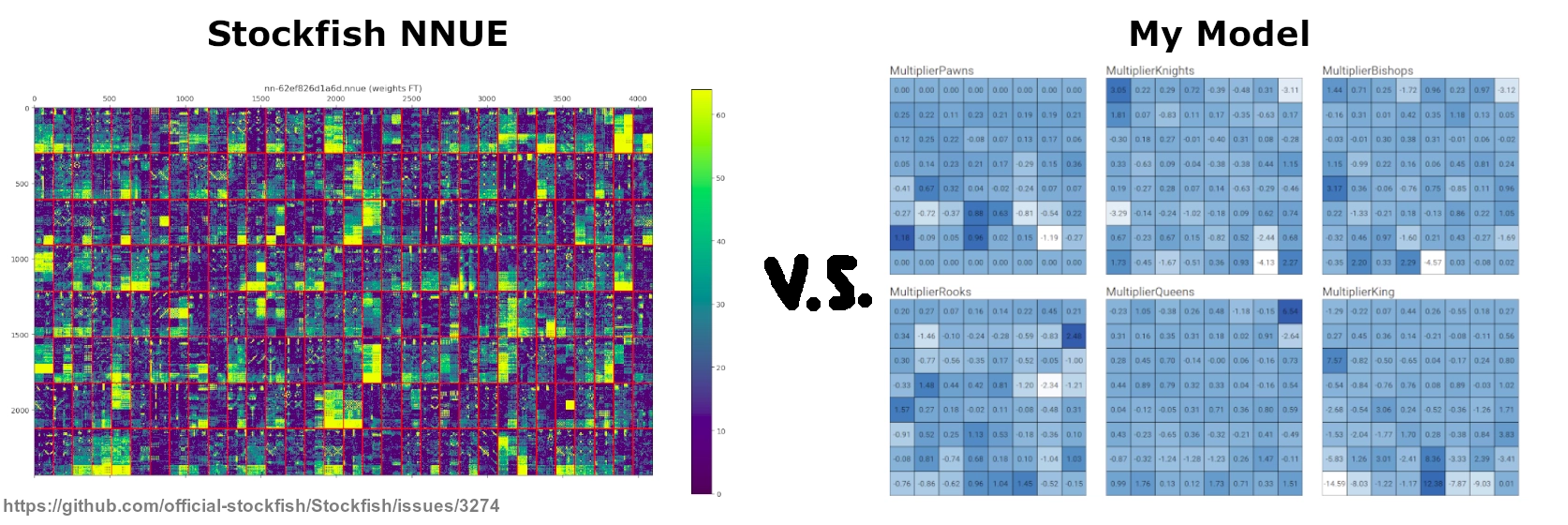

What was wrong? Distilling the knowledge stored in the NNUE, which is pretty small but still about 50MBs large, into only 24576 values was too much. The loss of context that my implementation had by design, was crippling it’s ability.

The model does not consider a piece’s position relative to others. Moving the queen to c6 would be evaluated as equally good, whether it blundered the queen to a pawn or delivered a beautiful checkmate.

But adding the additional context that Stockfish provides to it’s NNUE was simply not possible due to the constraint on the amount of tokens.

How does the NNUE solve this problem?

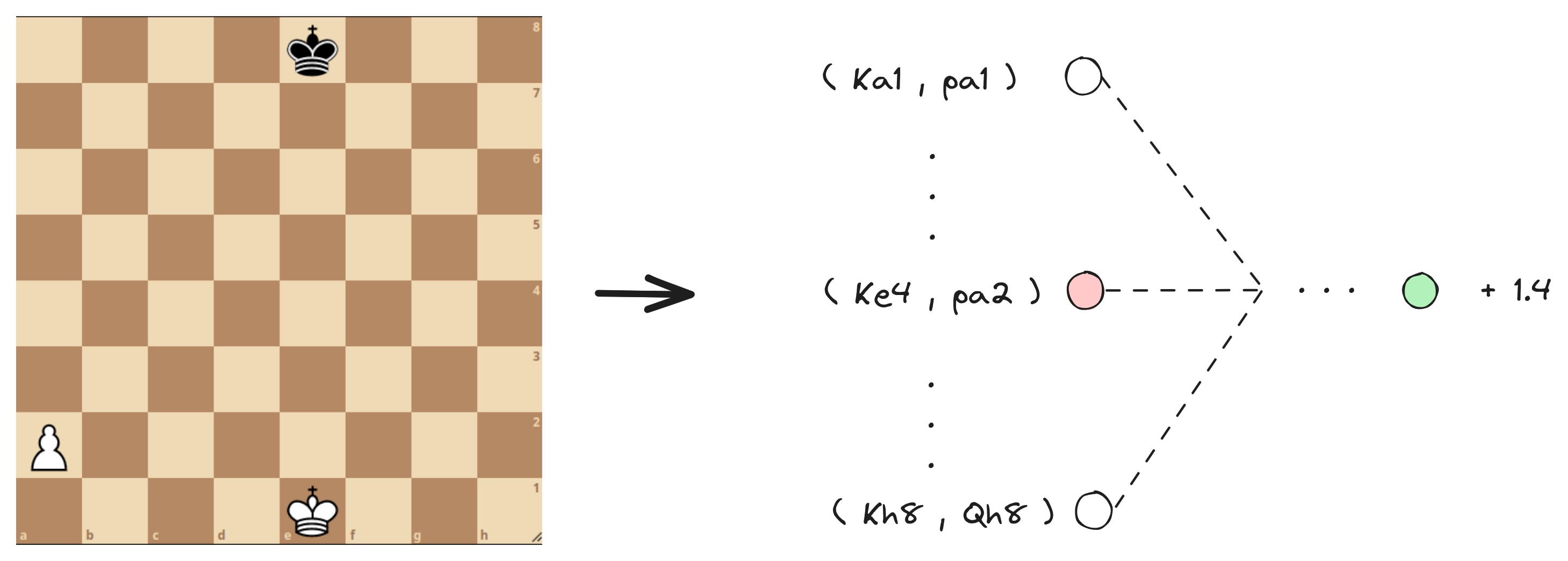

Stockfish’s NNUE is essentially made up of a heavily overparametrised input layer and a simple 4 layer network behind it. What this means is that instead of using bitboards representing the positions of the different pieces as inputs and applying the weights and biases, it instead gives the NNUE the positions of every single piece in relation to every single king position. This provides the network the necessary context to evaluate the position, which our simplified version lacked.

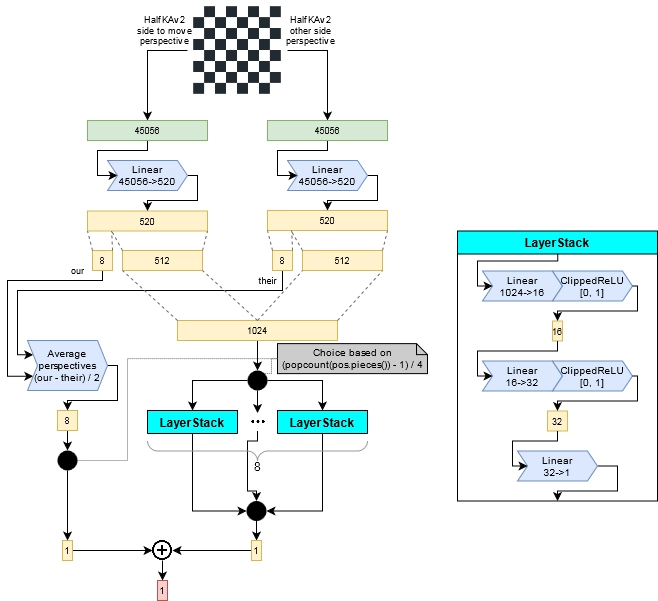

Concretely this translates to a model architecture consisting of 2x45056 inputs. It has two sides, one for the side that currently moves and the opposing side. Where does 45056 come from? For each of the two input halves, there are 11 other piece types to consider in relation to the king of the current side and there are then 64 squares a piece could be on for 64 squares the king could be on.

For example, if white is to move, there are 11 other piece types (W Queen, W Rook, W Bishop, W Knight, W Pawn, B King, B Queen, B Rook, B Bishop, B Knight, B Pawn) that have to be taken into account. For each of the pieces on the board, we would then get the pair of (king position, piece positions), and activate the corresponding input node of the network.

This graphic from the chessprogrammingwiki.org nicely summarizes the reset of the model architecture.

This architecture also allows the highly optimized evaluation of the network that makes Stockfish so fast. As long as the king does not move, you only have to update a single input node to recompute the evaluation for each move.

How could the shortcomings of my model be remediated?

While the ultra-high rate of compression from 2x45065 inputs to only 6x8x8 is clearly too high, a more conservative approach might be able to identify unused or less impactful inputs or nodes in the stockfish NNUE to apply a “pruning” of sorts. Some positions such as (…, pa1) and others where the pawns would have to walk backwards are not even possible and I assume naively (please reach out to discuss this idea and to correct me) could easily be removed from the network.

Addendum

EDIT - 08.10.2024: I added this section to highlight some interesting technical behind the scenes information. If you are interested in building your own chess engine or in debugging complex recursive algorithms, I recommend reading the section about debugging on GitHub and others in my README.md. I tried to summarise the most interesting parts below.

Debugging

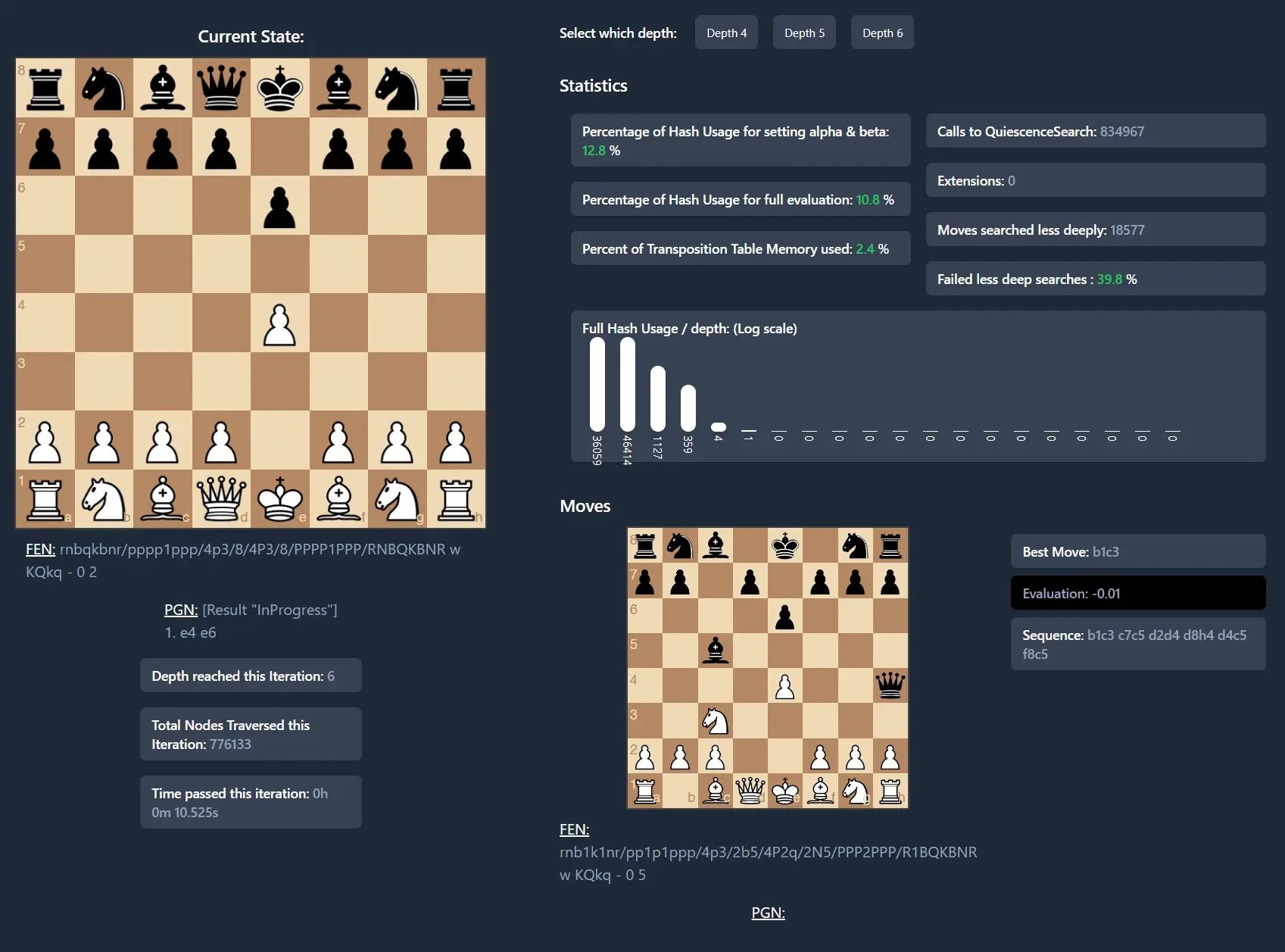

The dashboard I built to debug my own application shows depth reached, the amount of nodes traversed and the memory consumed by hash tables storing certain evaluations among others. I found that these were the most critical pieces necessary to debug issues.

The engine dumps this information into a JSON file with each iteration, which is picked up by the server and refreshes the dashboard. Monitoring applications this way is common in web development, where distributed systems are otherwise impossible to debug. But to my knowledge, displaying a system’s health status and other vital information is not as common in other fields, which may benefit.

The information on the bottom right is especially helpful to debug some complex issues with mates. It shows the best move chosen and the evaluation, but also the sequence of moves the engine explored to determine this course of action.

Inspection of deeper internal states allows us humans to understand the engine’s rationale for a certain move. For example, by visualising the final state of the board at depth (if both players play optimally).

Beyond pruned Minimax

I also wanted to add more detail about advanced techniques for engine programming that I came across.

After setting up your basic minimax framework, you are then free to have fun. There are tried and tested algorithms, but it’s especially fun trying to tack DIY additions onto your progressively more powerful engine.

Below is the list of optimisations I implemented, as they are the lowest hanging fruits.

Transposition tables

To avoid wasting cycles by recomputing the optimal move for nodes that were already visited, the engine uses transposition tables. A hash of the board is used as the key under which the best move (as calculated at depth ) is persisted.

The dashboard also allows us to inspect the usage rates of the transposition tables, which is interesting for optimisation and sizing the table.

Quiescence search and search extensions

Sometimes, stopping the search at depth is harmful to the evaluation, as the board is in a “hot” state, where both players are trading pieces. In these cases, it makes sense to extend the search a bit further, until the evaluation stabilises.

This is the problem quiescence search solves. By continuing the search just a bit longer, the engine achieves more accurate results. It works by only exploring captures, until there are only normal moves left. If we didn’t perform this type of search extensions, some unrealised threats wouldn’t be included in the analysis. For example, a pawn threatening to take a queen in the next move wouldn’t matter at all if we stop at the depth just before, as the lost queen wouldn’t be included.

Time management and early exit

A very difficult aspect of designing an engine is deciding on the amount of time to give it for each move. A basic example would be allocating more time in the endgame to catch a mate that otherwise might be missed. My approach to this issue is documented in the readme, but I am not happy with my results.

The final moves of the game are very important, as an engine not allocating enough computation time here, might miss a certain mate. On the other hand, saving up time during the mid-game might ensure that you don’t even reach the end-game in a position to mate the other player. If you don’t let the engine evaluate complex mid-game positions deeply enough, it will quickly lose.

This balance is hard to correctly identify and there is not too much information about this on the web or various wikis.