Try out the games yourself at spiele.obrhubr.org.

I enjoyed solving the daily New York Times puzzles, then I found the daily Quordle and then the daily Waffle and soon after the daily LinkedIn puzzles. And before I even knew it, the entire thing got out of hand (I would only slightly be exaggerating by saying that I spent the entire day puzzling).

To convert this daily ritual into something more meaningful - and educational - I decided to build my own version of my favourite puzzles: Connections. But I wanted to add a twist and after some deliberation settled on creating a German version (because it’s my mother tongue).

I sent my first puzzle - or “Verbindung” as I like to call them - to a good friend and he was hooked. He responded in kind, but his was way harder! And soon we shot puzzles back and forth, trying to outsmart the other (he won).

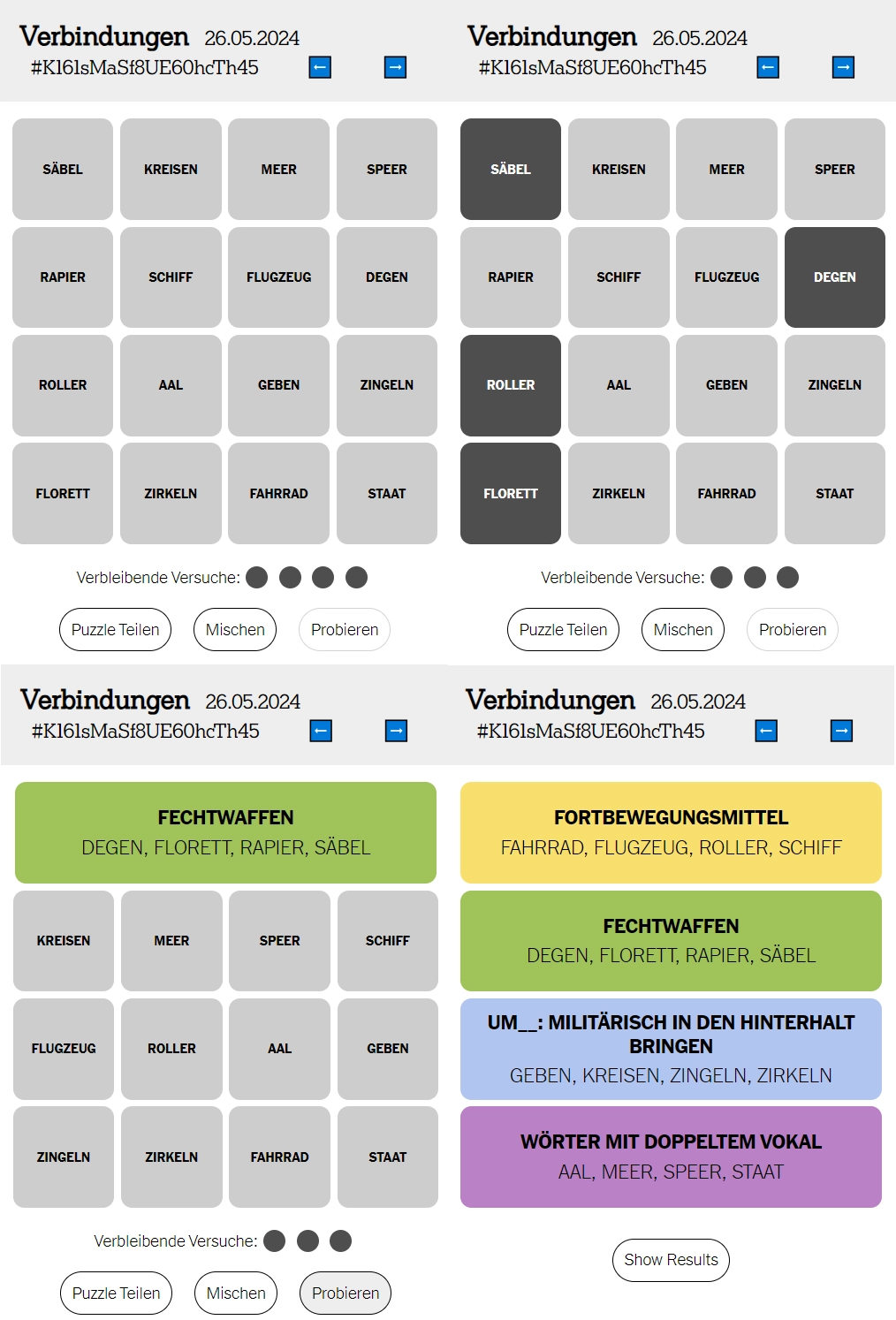

The game

When first loading the site you are presented with the blank grid of 16 words of today’s puzzle. There are four categories - with four different difficulties - each with different titles, and four words each that fit into them respectively. The objective is for you to find the words that go into each category. You can read the entire rules at www.nytimes.com/games/connections.

A short taste of fame

I soon added some basic level of analytics, giving in to my urge to collect data everywhere and from everyone. The site would store the game history, mistakes made and if it was solved. This proved very useful later…

A friend encouraged me to post the site to the r/de and r/austria subreddits. At first the posts racked up views and upvotes (2.1k views in total), but I was quickly yanked back to reality by the moderators of the communities.

They - in typical reddit fashion - reminded me that self-promotion is strictly prohibited by striking me with the ban hammer. Even though I was not selling anything, which I also told them, they were adamant on keeping their users safe from my posts.

I accept that of course, but it’s a bit sad as people seemed to enjoy them. We got several comments, my favourite being: “Ich liebe es 😡 aber mein Telefon landete schon 2* an der Wand.” which translates to “I love it 😡 but I threw my phone twice against the wall already.”

The actual impact of this short stint on reddit were 310 new users in total, playing a grand total of about 140 games. Not a bad conversion rate…

Tracking user behaviour

After the massive - a new dimension for me at least - influx of visitors died down, I was left with a database waiting to be analysed. I was only briefly interrupted due to passing my final exams, but now it’s time to get some insights out of raw data.

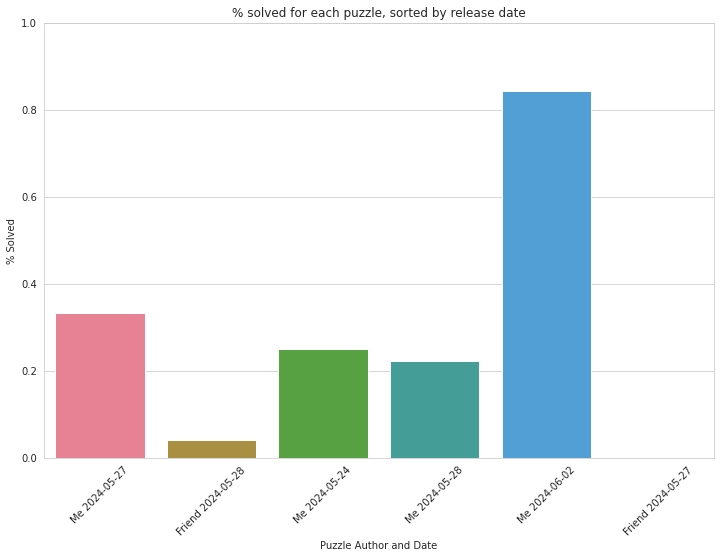

1. The most important question was of course: who makes the harder puzzles?

Knowing that all puzzles were played at least ten times, I think this graph truly speaks for itself:

You can see that the puzzles I created were solved at much higher rates than those my friend created. He is either making fiendishly difficult puzzles on purpose or is smarter than all of us.

But now I also now know that the puzzle published on the 2nd of June shouldn’t have been that easy.

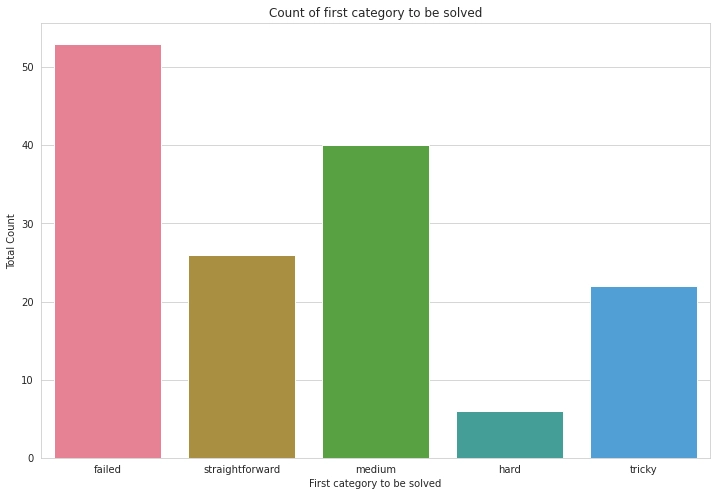

2. The next question that begged to be answered was: How well did we choose the difficulties of the different categories?

In a perfect world, we would like to see the straightforward category to be solved first and most often, then the medium difficulty, etc… But estimating difficulty is very hard, and this was reflected in the data.

The graph shows which categories were solved first and how often. Clearly, most users found the tricky category easier than the hard one, and by a large margin. Also somehow the medium difficulty one was easier than the straightforward category? This was something I did not expect.

3. Words from what category trick people most often?

Another interesting fact, which confirms an assumption you would instinctively make, is that words from the tricky category are most often confused for words from other categories. 37 incorrect guesses included a single word from the tricky category. This is in comparison to 4 in the medium category, 4 in the hard category and 2 in the straightforward category.

4. In what order do people solve the puzzle?

Another interesting observation is that the most common order in which people solved the puzzles were:

1. Medium -> Straightforward -> Hard -> Tricky (total: 19)

2. Medium -> Straightforward -> Tricky -> Hard (total: 9)

Which at least tells us that Medium and Straightforward are - as expected - the easiest.

But there is an interesting phenomenon, the second most common order is to only solve the tricky category and nothing else, with 12 occurrences. This seemed bizarre at first but we can actually learn something important from this.

The title of the tricky categories which were immediately solved were: “Words in James Bond titles” and “Words from Goethe’s book titles”. In hindsight, these are very obvious to people who have a bit of general knowledge - and Goethe is very famous in Germany and Austria.

(You can play the puzzles these are from at this link on spiele.obrhubr.org and this link on spiele.obrhubr.org)

What makes a great Connections Game?

So one thing we learned about great puzzles: They don’t use obscure general knowledge for the tricky category. Instead we should actually make them tricky, by forcing the player to think outside the box. An example from the New York Times (play here) for this would be “JEWEL”, “OM”, “CARROT” and “HURTS”. Did you guess the name of the category? It was “Homonyms of units of measure”.

This type of relation is very hard for computers to imitate, which is why we probably won’t see any Connections created by ChatGPT soon…

Analysing the puzzles made by the NYT with embeddings

The source of truth for great puzzles are the official ones made by the New York Times - mostly because there is someone getting paid to think of new ones all day.

There is a technique from machine learning which allows us to compare how similar words are: embeddings. By getting the vector representation for each word and using cosine similarity, we can get a number that quantifies how semantically close two words are. This misses any phonetic similarity of course and loses nuance, but it’s a good approximation.

Running this algorithm on the puzzles I scraped from the great site Connections+ confirms another intuition. The words in the easier categories are more semantically related than those for hard or tricky categories. Most importantly, the words in the straightforward category are a lot more semantically related than the words in the other categories.

This makes sense because the relation between words in harder categories is often an indirect one, for example as first words in a pair, such as FIRE ___: Ant, Drill, Island, Opal.

Finding the hardest puzzle from the NYT

Another thing this algorithm allows us to do is quantify how hard a puzzle is. We can assign a score based on how closely related words in a category are and how dissimilar they are from the others. This algorithm actually works pretty well, which surprised me.

The hardest puzzle is #49 from July 29, 2023 and the easiest is #28 from July 8, 2023. When you look at both, #28 is way easier, because all categories are ones that are semantically related.

Procedurally generate a Puzzle

If we can score puzzles by how hard they are, we can also generate puzzles that are arbitrarily hard, can’t we?

We start by choosing a random word from the dictionary and getting the most similar ones by using embeddings. We remove those that are too similar (by stemming, which means “likes” and “liked” will be removed, and lemmatization, which means “better” and “good” will be removed). This leaves us with a list of words that are semantically but not orthographically related.

We then pick another word, which is not too different but not too similar semantically and repeat the process of choosing three other words.

Repeat until you are left with 4 categories: (This is a real example)

-

“woo”, “lure”, “entice”, “attract”

-

“gathered”, “congregated”, “flocked”, “converged”

-

“adage”, “axiom”, “truism”, “proverb”

-

“Corgi”, “Shitzu”, “Pomeranian”, “Bichon”

This is not a very good Connections puzzle, but it is a playable one. And if you aren’t a friend of mine who likes to create too difficult puzzles (you know who you are!), a playable puzzle is better than an impossible puzzle and most of all, better than nothing.