A while ago a friend messaged me, asking me to report his hacked Instagram account. When his account reached out to me on Instagram a few days later, I had all but forgotten his warning.

The message came in around midnight on a Friday, the scammers imploring me to cast a vote for “my friend” in a competition. It also came with instructions: a link and the demand for a confirmation screenshot.

The site the scammers pointed me to was hosted on Vercel, under a free xxxxx.vercel.app domain. At these first signs, alarm bells already went off in my head. Most obvious was that the their cover story didn’t match what was on the site.

But this being midnight, I didn’t fully process any of that and simply clicked on the Vote with Instagram button. This led me to a very faithfully reproduced sign-in screen. But no redirect to Instagram, which meant no password manager filling out my credentials. That confirmed to me this was a scam, jolting even my very sleepy self awake. This is also where I remembered my friend telling me about his account having been hacked…

Now I wanted to investigate. After entering fake credentials, I clicked on Log In and was shown an error pop up.

This is quite smart because it tricks people into typing their password again and again, which reduces the number of mistyped credentials they get. And you be skeptical if this actually works, but as you’ll see the data does back up this strategie’s effectiveness.

Asking for a screenshot to confirm their vote is probably also an ingenious social engineering tactic? People can’t just pretend they voted, they have to actually go onto the site, because they don’t want to refuse their “friend’s” demand.

Who are they?

The message I got was in the same language as the previous messages in the chat. That either means the scammers are from my country, or are using a more sophisticated method to target their victims. I couldn’t actually figure out if they change their message dynamically depending on the chat’s language, but ChatGPT might make things like this really easy.

However, I could identify their nationality after a friend of mine was able to recover his account. The phone number newly linked to the account indicated that the scammers were Nigerian nationals, or at least using a Nigerian phone number, because of the +234 telephone area code. That strongly implies they are using translated texts in an attempt to appear more authentic.

Looking at their Infrastructure

The phishing site used a Firebase real-time database to stream the credentials to their backend, which is a pretty smart way of setting this up. Because the data is then not only persisted in the database, but also on the machines listening to the stream. Thus, a vigilante hacker that deleted their database wouldn’t have any impact.

There is also no way of stopping them from getting the credentials. If they had set up polling on a traditional database, you could have deleted the data quick enough for them not to receive it. But by streaming it, all listeners are sent the same data and guaranteed to receive it.

The only thing you can do against this, is to send a constant stream of realistic fake credentials and hope they can’t filter out the trash. This would also help in case they had set up an automation to login with the phished data without manual oversight as it might trigger an IP block from Meta.

How many people fall for this

Something I neglected to mention until now is that they hadn’t set up any access control on Firebase. They logged all data coming in, directly on the client. This meant that I could watch while people where getting phished. Thanks to this, I was able to alert victims I knew to the fact they had been phished. Thankfully, for a few people this actually worked and they were able to change their password fast enough.

I exfiltrated the data and began analysing the victims behaviour, in order to better understand how and why people fall for this kind of basic phishing. I collected a total of about 700 distinct login attempts, over the span of a week.

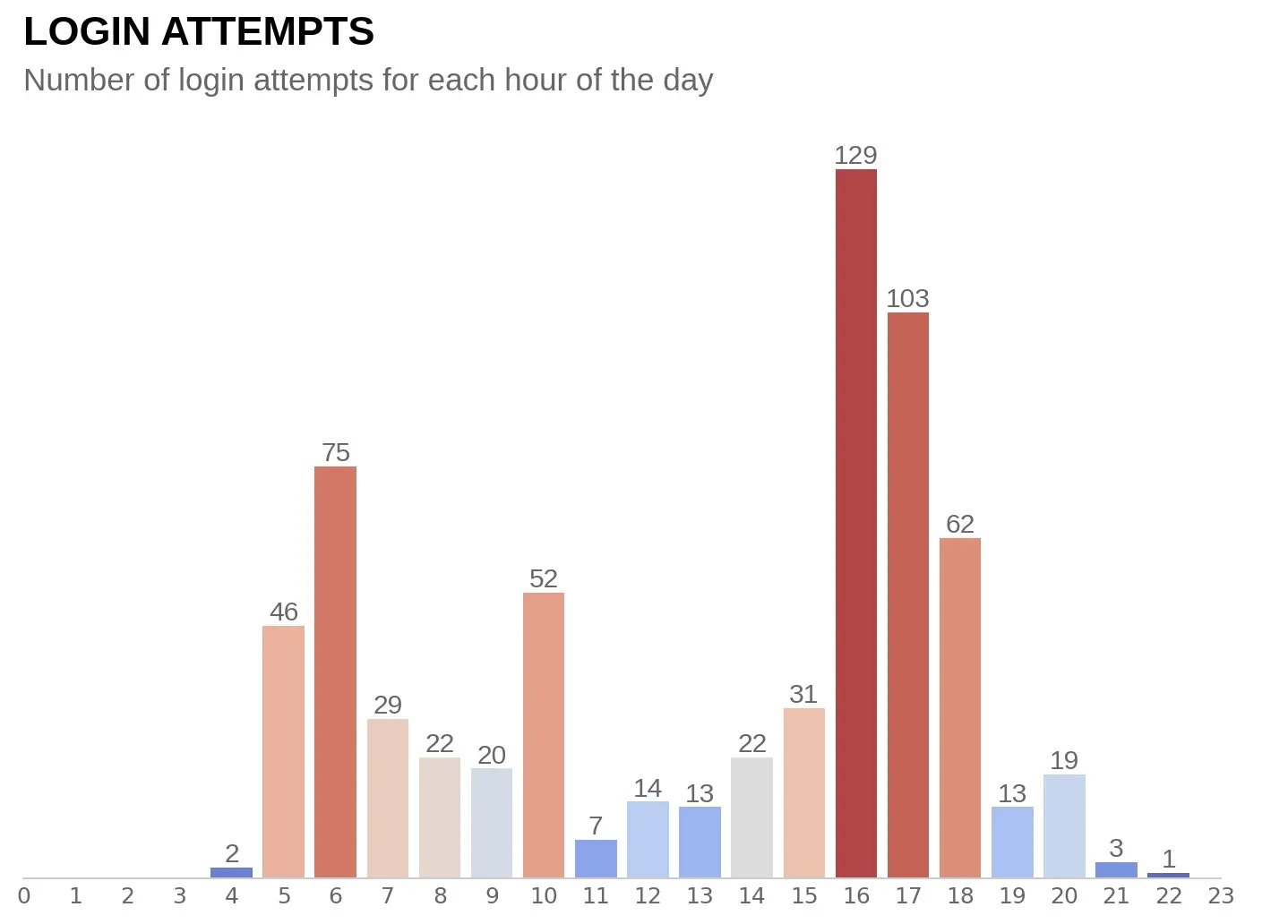

The first thing that stood out to me was the time (localised for each victim) people visited the site. Most were phished early in the morning or in the evening. We could either explain this by assuming most people don’t check their phones during work hours. Or we could draw the further-fetched conclusion that people are more vulnerable at odd hours, when they are potentially more tired.

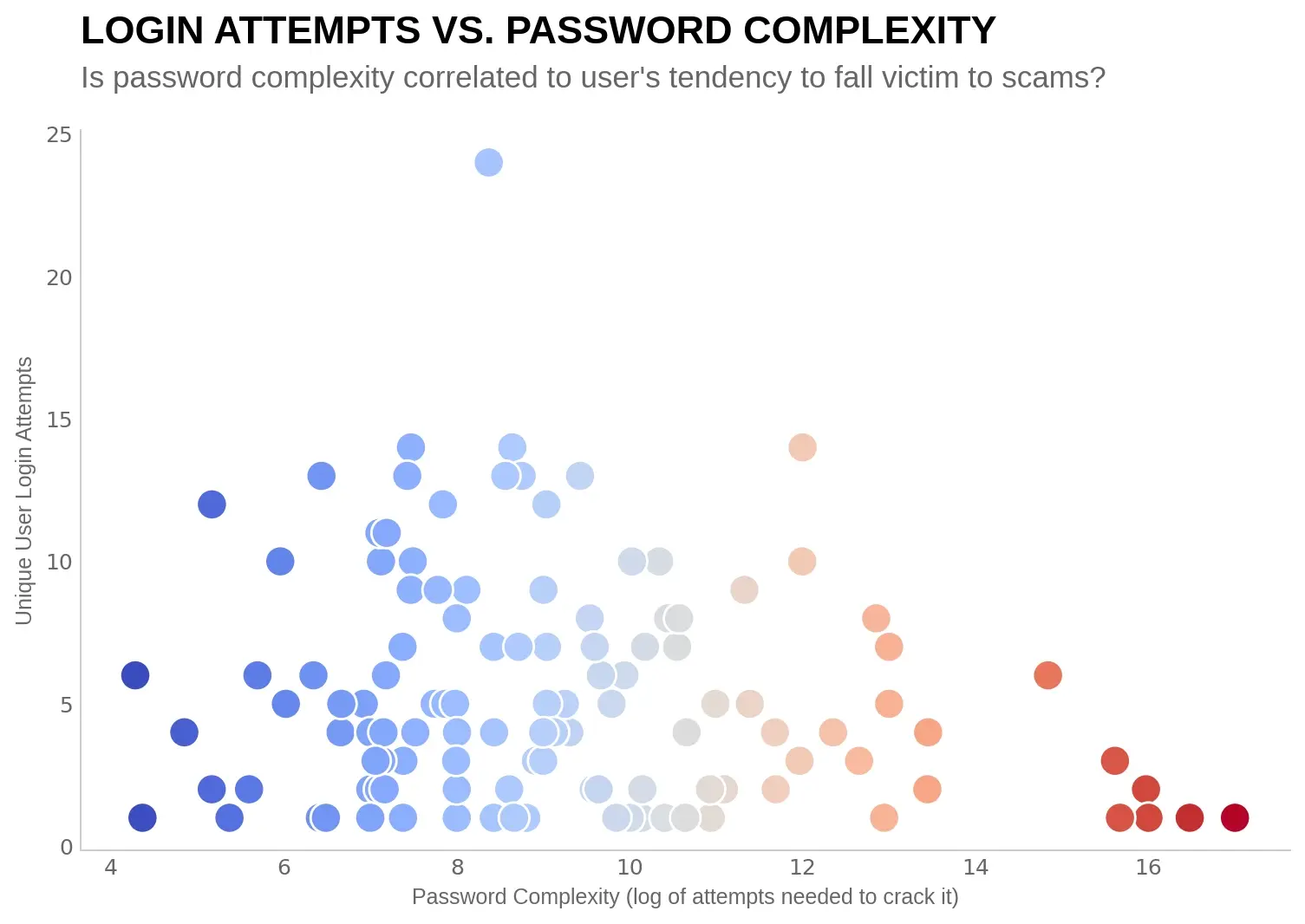

Remember how the site shows Something went wrong while casting your vote, to trick less technically versed people into logging in more often? If you are tech-savvy enough - using a password manager or at least having better security practices - you should in theory not fall for such a simple phishing attempt. The data, as plotted below, seems to support the conclusion that users falling for this are less tech-savvy (by this crude metric).

The graph below plots the amount of times a user logs in against the complexity of their password. To count the amount of times a person signed in, I grouped the credential pairs by matching them over multiple log in attempts. If the data shows an attempt with login_a and password_a and login_b with password_a, we know they belong to the same, “real” user. Two more things stand out: there are less users logging in with very complex password and they become aware of the scam quicker.

After the phishers compromise the first account, they spread virally through the victims social network. With every new person they infect, they can spread to their followers. I tried to visualise this process, plotting the victims locations over time on a map. A pattern of slowly spreading out from the root to other cities is visible.

There are a however also some users that noticed that the site was a scam and used credentials like NoHacker123 to protest. Another person tried to convert the sinning scammers to Christianity by sending them the password repentnowcauseJesuslovesu.

Getting back at them

Reporting this issue to the hosting provider Vercel was very easy and I got a response only a few hours later. About 24 hours later, the site was taken down. This probably won’t stop these people, because they’ll just set up a new site and a new Firebase account to get started again, but at least it’s extra work and might slow them down.

Update from future me: They have set up the exact same site only about a day later, but under a slightly altered domain name - again on Vercel.