After writing my own version of the NYT’s puzzle Connections, the Mini-Crossword was next. But the challenging part was not writing the crossword player for my site spiele.obrhubr.org, it is constructing the puzzles. But surely I can automate that…

Crossword Rules

There are many types of crosswords - that differ based on the rules for construction - and depending on where you live, some might be more familiar. This article will be focusing on American crosswords.

The most important rule for this type of crossword is that every square must be included in both an across and down word. The black squares must be symmetrical (the puzzle must look the same upside down as right side up).

There are two publication specific rules: For the New York Times’ crossword, famously edited by Will Shortz, there are very specific rules. If you are interested in more general advice around constructing, have a look at this post by Lloyd Morgan, which I found very insightful.

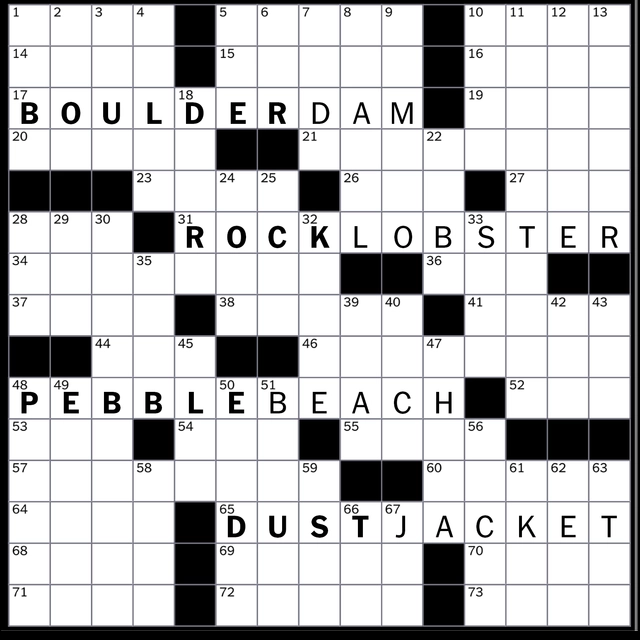

So what does the process of constructing a crossword look like? To get started you have to find a few words which will be the “main” entries in your crossword. They might be themed (connected by a common thread) or just plain interesting to you. This is the creative part!

However, after placing your main entries into the grid, a lot of white space is left to fill. This is where it gets difficult for an amateur. You might start and fill in a few words, but soon there will be spots with seemingly impossible to fill squares.

You can try to work around this by using online tools like searchable dictionaries, but you will still find that you constructed yourself into a corner or have to resort to very obscure words.

Filling the Grid

This is why most online constructing tools (I recommend Phil or Crosshare) or more expensive desktop software (like Crossword Compiler) offer tooling to fill the grid for you. This is where it gets interesting for me, because now there’s software involved.

These tools use something called a “scored wordlist” to fill the grid using an algorithm. A scored wordlist is like the secret sauce in the world of crossword constructing - and most you actually have to pay for. They contain a list of words and a score for each, based on how “crossword friendly” it is. A very popular free wordlist is Peter Broda’s Wordlist. To give you an example “APEXPREDATOR” has a score of 100, where as words like “AES” have a score of 11.

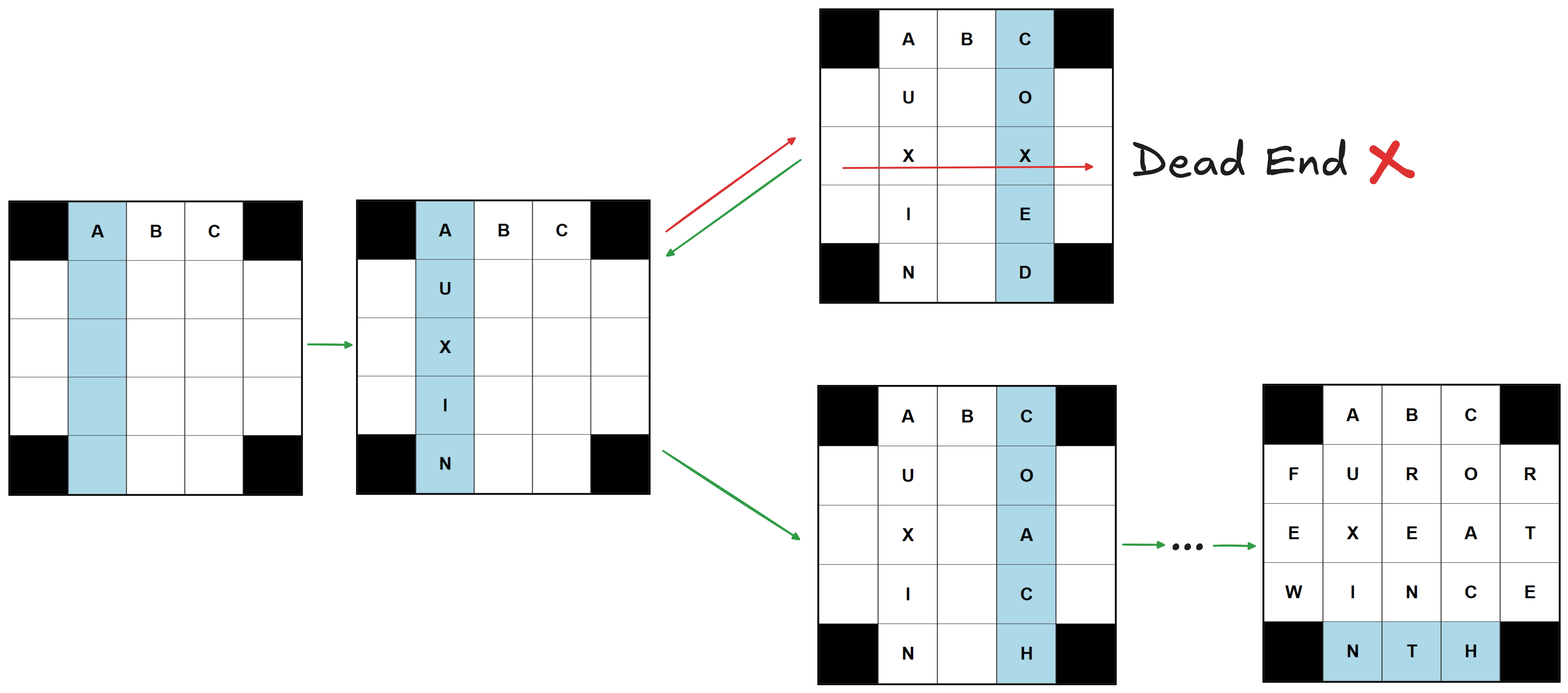

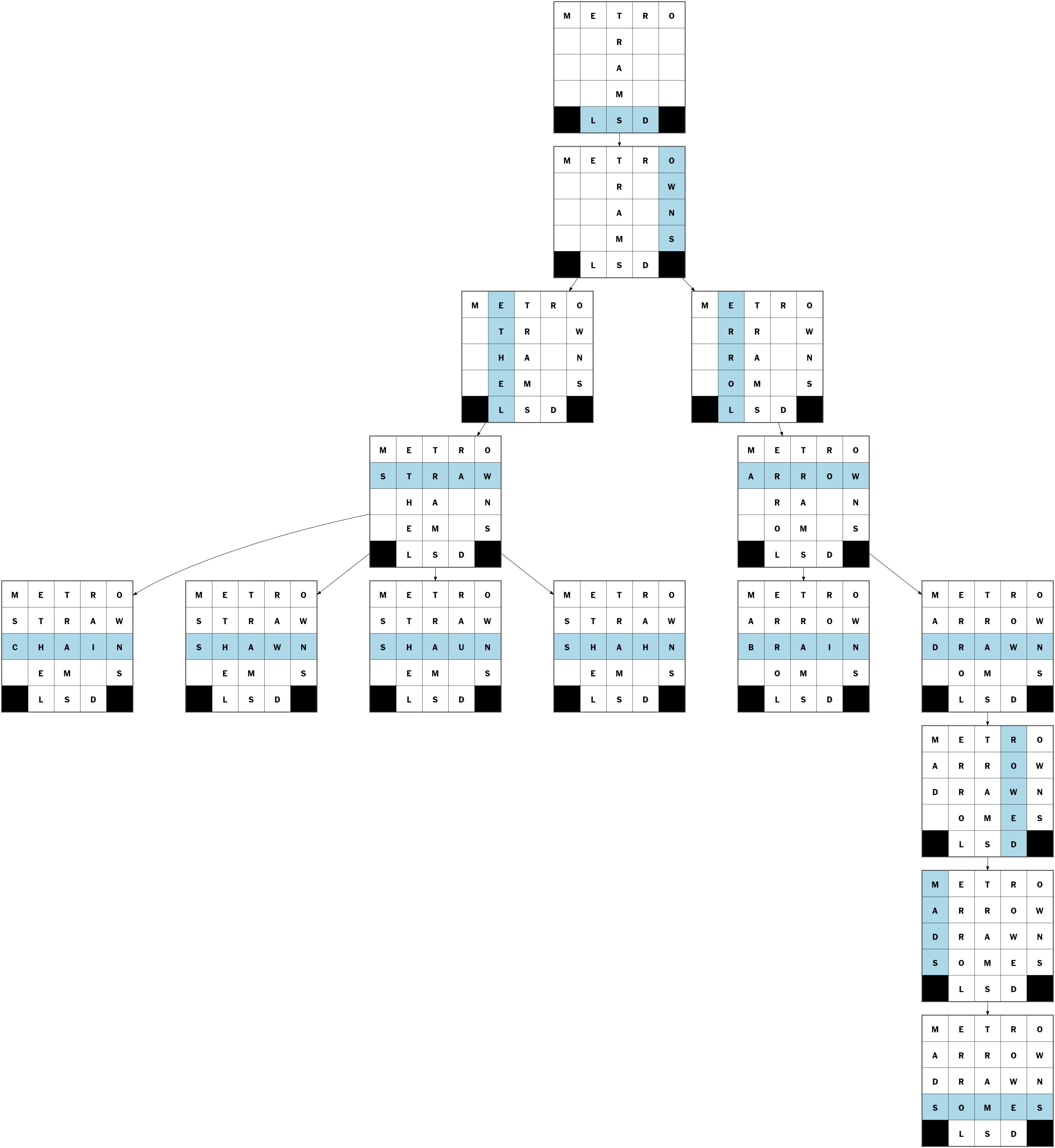

Now how do I get from wordlist to a filled puzzle? There are a few different algorithms floating around but the simplest approach seemed to be a recursive one, using backtracking.

Backtracking works by filling in the words one by one. Once you hit a dead-end - in this case a grid that cannot be filled anymore - you go back one step and try the next word. Repeat until you have a fully filled grid. I implemented the algorithm in python, take a look at github.com/obrhubr/xword-fill. The basic implementation of this algorithm works very well for this task, but is painfully slow (almost 25s for a 5x5 grid).

To visualise the process a bit more, I wrote a little script that extracts the tree that the solver travels while filling the grid. This is what a real example of filling a 5x5 grid looks like.

Optimising the Backtracking Algorithm

The easiest crossword specific optimisations here are to choose the highest scored words first and introducing some randomness into your alphabetically sorted word list. If you don’t, you will be left with a grid that has a lot of A’s in it.

A bit less obvious is the order in which it fills the grid. It should always pick the most constrained word, meaning the word that currently has the least matches in the wordlist. For example, if you have “_ _ R _ “ in your grid, there are going to be at lot more possibilities than for “_ X _ X _”. This cuts filling time down by a lot.

After playing around a bit, I found that for me crosshare.org’s algorithm is the fastest. This is due to their search algorithm being very sophisticated.

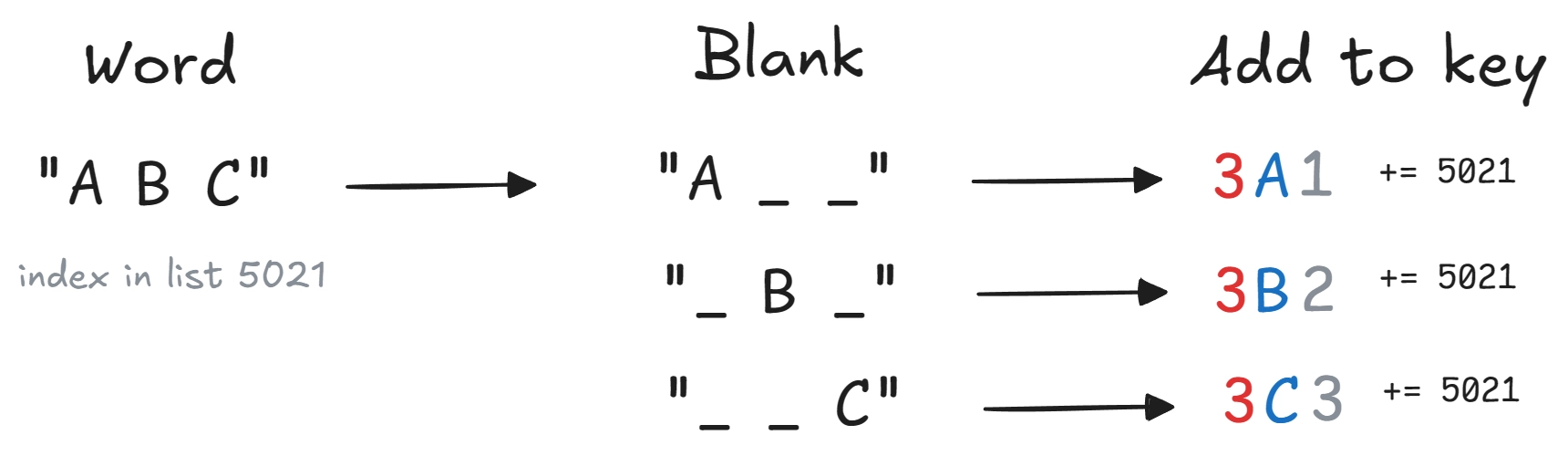

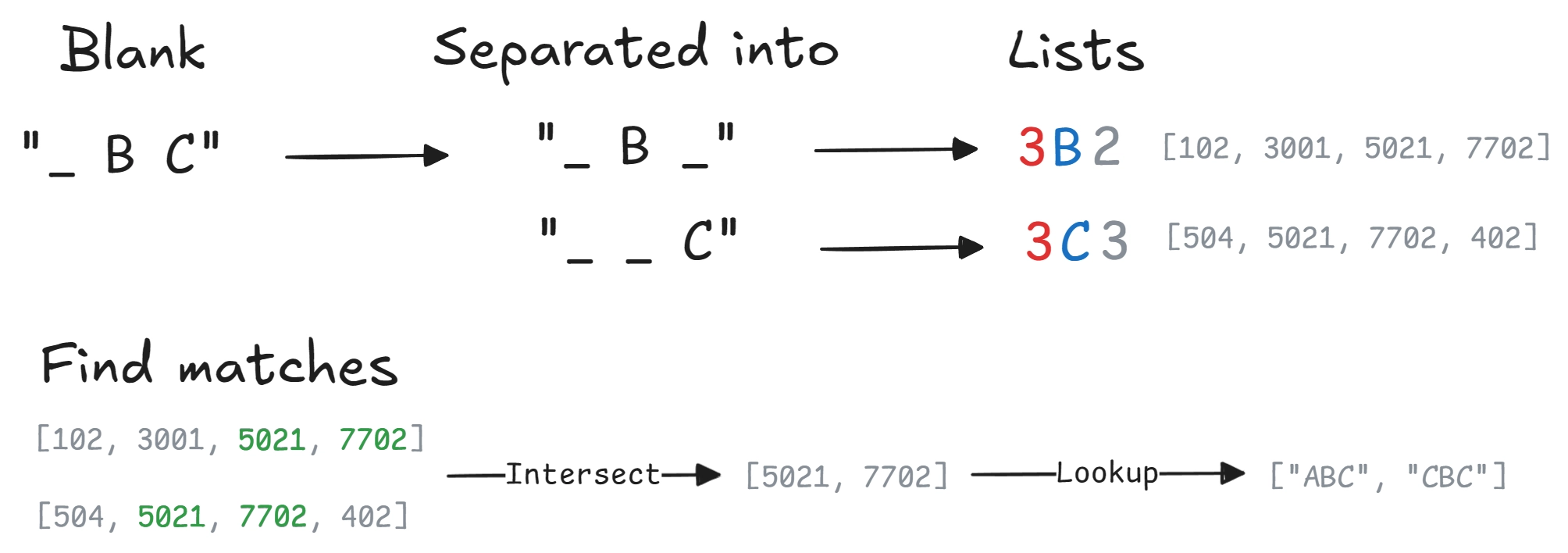

Instead of iterating through every single word in the list and looking for the ones that match your blanks and letters, they trade size for speed. Their solution is to use what they call a “WordDB”, which is just two giant lookup tables.

The first lookup table’s key is the word length. Now, instead of searching the entire wordlist, you only have to search for words of the correct length.

The second is a bit more complex. The key is: word length + letter + position of letter. That means that each word has as many entries in the DB as it has letters. The word “KANGAROO” would be stored under 8K1 and 8A2 etc…

So how do we use the lookup tables to find the words matching our grid? Let’s say we need to fill in the following word in the grid “_ B C”. It first get separated into two distinct searches, “_ B ” and then “ _ C”. We then convert these to the format of the keys in the second lookup table. “_ B ” gets converted to 3B2 and “ _ C” to 3C3. Under each of these keys, we find a list of indices that point to words in the first lookup table. But since we are only interested in words that match both of our constraints, we have to find the words that are stored under all keys. And there we have it, only words matching “_ B C” are left.

The Wordlist

I should have everything now to create some fun crosswords - in English. But to construct German puzzles I still need a German wordlist. After a bit of searching I found people asking similar questions on forums, but didn’t have any more luck getting my hands on one.

The first step in creating my own wordlist was finding a complete list of German words. This is harder than it sounds because of German’s unique way of constructing words: you can chain together nouns into a new, longer word. This means that theoretically, there is an infinite number of words that can be created. To get a non-exhaustive but practical list, I used the open spellchecker aspell’s dictionary that conveniently also contains conjugated forms of root words.

I had some cleaning up to do before we could use it. First, I filtered out words with numbers in them and transformed the umlauts (e.g. Ä, Ü, Ö) into their expanded forms by appending an “e” (e.g. ae, ue, oe). Finally, I removed any word longer than 21 characters, which is the maximum size of NYT crosswords (the Sunday size).

Now the interesting part: scoring the words. The site Crossword-Compiler suggests that fairly common words be scored with 50, less common words with 25 and vulgar words with 10.

For my wordlist, I assigned a score of 50 to all root words from the aspell dictionary while their derivates got a score of 25.

To improve this rather basic scoring even further, I used a list of words and the number of their occurrences by the university of Leipzig. Words that are used more often have their scores increased slightly, less used words see their scored reduced. For example: PHAENOMEN has a score of 55, as it’s a root word and is used fairly often. PIESACKEN - even though it’s a root word - is rarely used and thus has a score of only 40.

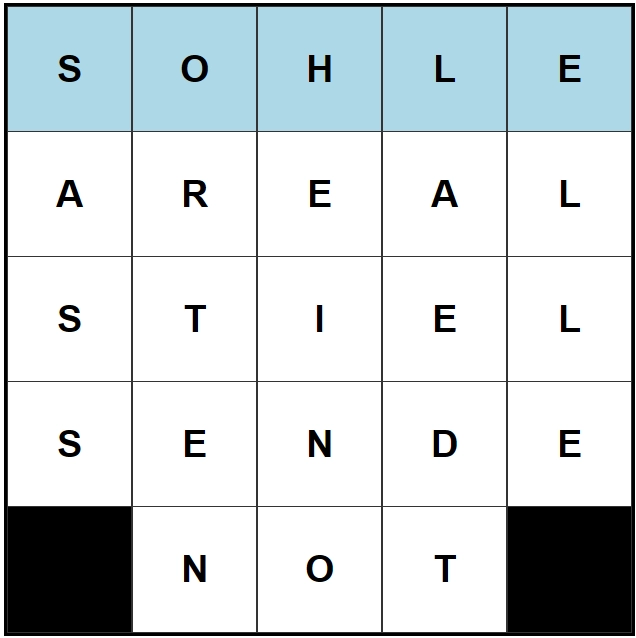

You can download the list here github.com/obrhubr/deutsche-kreuzwörter. And voilà, the fruits of our labour, a filled German crossword, revealed in all it’s glory:

How to Write a Crossword Clue

The next step a cruciverbalist has to take before releasing his puzzle is to write the clues. This is more of an art than a science, as they have to gently guide their reader to the solution. In order to get some insight into how popular publications clue their crosswords, I downloaded data available freely on the internet.

Parsing Puzzles in different Formats

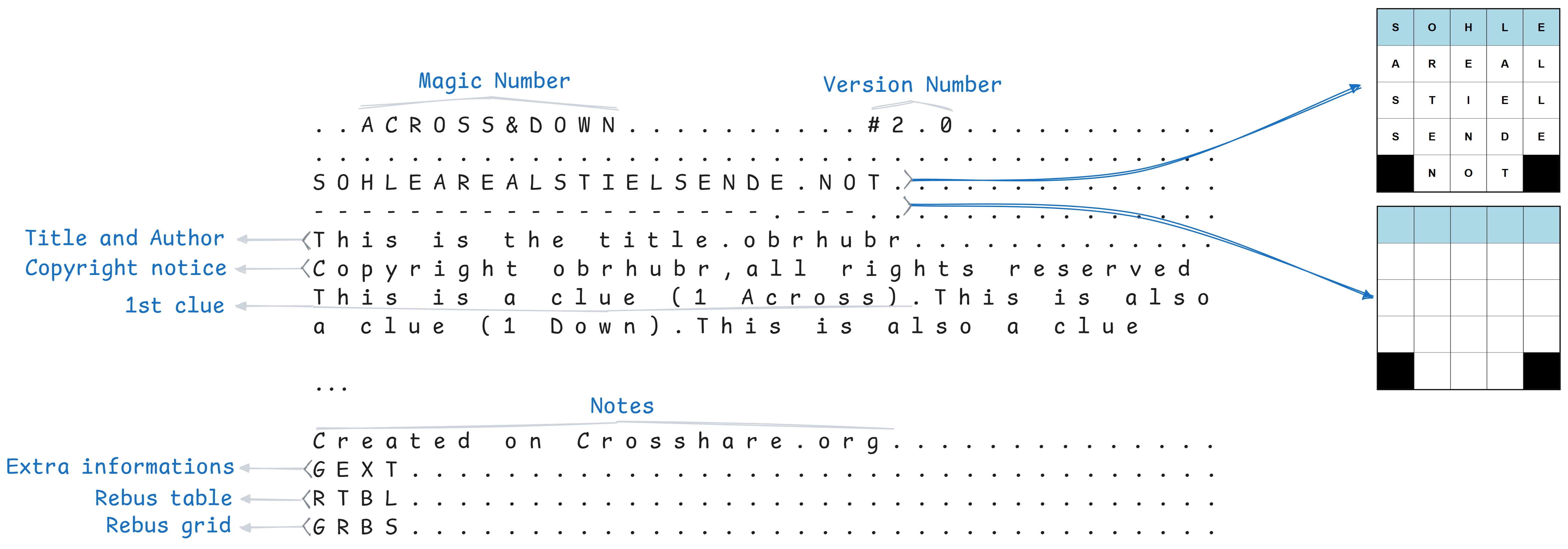

However, some puzzles were provided in .puz format, which was created for the crossword software Across Lite. The complete format is outlined here, but we only care about importing the data. I wrote a python cli utility to convert them and extract the data I need, check it out under github.com/obrhubr/xword-converter.

The puzzle.puz file is a binary file. Converted to ASCII the file looks like this (the . represent invalid ASCII chars):

At the top ACROSS&DOWN is the magic number that identifies this as a .puz file. It then contains the solution and the player’s current progress, the metadata, clues and any additional information like rebuses and circles in null separated strings.

There might be advantages to this format but ease of use is not one. There are checksums everywhere which seems overkill for a small puzzle file. Even better, there is no official documentation. It’s also impossible to represent some more esoteric choices that the NYT sometimes makes (such as words that are neither across nor down but heart shaped or a grid made to look like a pizza).

Analysing the Clue dataset

Now that we have raw data available (1 133 373 clues and 138 144 unique words), we can proceed by analysing it to get some insight into how to write a clue.

Fill words

An unpleasant but necessary part of constructing is filling the small spaces, 3 or 4 letters long, with something interesting. Often, the same words are used over and over (see relevant xkcd) and thus clueing them with something innovative is really hard.

The most used word in my dataset is ERA with 878 occurrences. Inventing a new way every time you have to use it is very challenging. “Historical period” for example, was used most often to clue it (19 occurrences).

Clueing over time

Another interesting observation we can make is that the way words are clued changes over time. The word ERA can also be understood as “earned run average”, a baseball term. We can see a decline in usage of clues relating to this meaning over the decades:

| word | decade | counts | |

|---|---|---|---|

| pitcher | baseball | 1990 | 6 |

| pitcher | baseball | 2000 | 7 |

| pitcher | baseball | 2010 | 3 |

| pitcher | baseball | 2020 | 2 |

Maybe this reflects a more general trend (reflected in google trends)? Or this might be the sign of crossword publications shifting towards a more international audience?

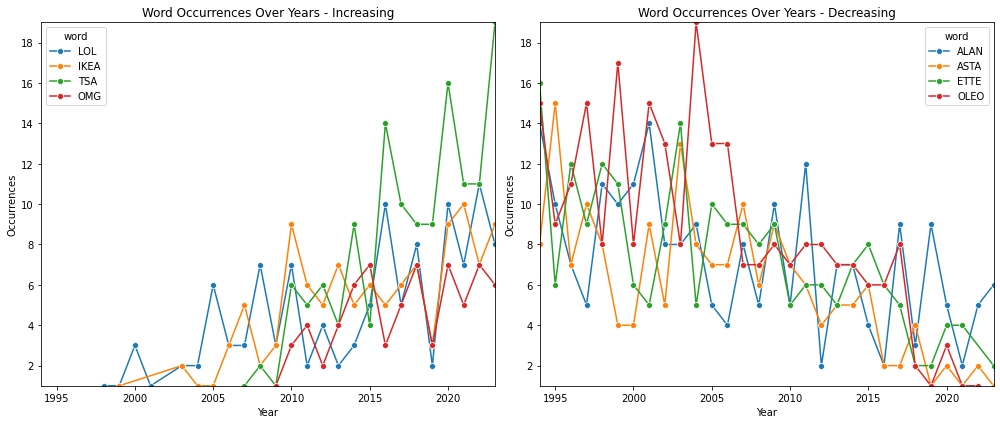

Another fun observation is the appearance of new words. TSA was first used on the 19th of February 2007. IKEA similarly increased in popularity as the brand’s recognition grew in the USA. Trend words such as LOL, OMG and other online abbreviations also see an upward trend.

Word usage also correlates with companies popularity, AOL for example saw it’s usage increase into the 2000s and then fall again.

Analysing Clue difficulty

Quantifying the difficulty of a clue isn’t possible directly, but we can use text embeddings as a pretty good heuristic. This technique, which is a core component of LLMs, consists of figuring out the vector representation of a text in semantic space. This embedding vector can then be used to quantify how similar the meanings of words are.

Note: You can also perform algebraic operations on the embeddings, as you can try out here.

The hypothesis is that the more similar the meaning of the clue and the word, the easier the clue. For example, the word OFTEN and it’s clue “Frequently” are the most similar out of all the clues in the dataset. For comparison, the least similar word-clue pair is CCCP and “Letters on old Soviet rockets”.

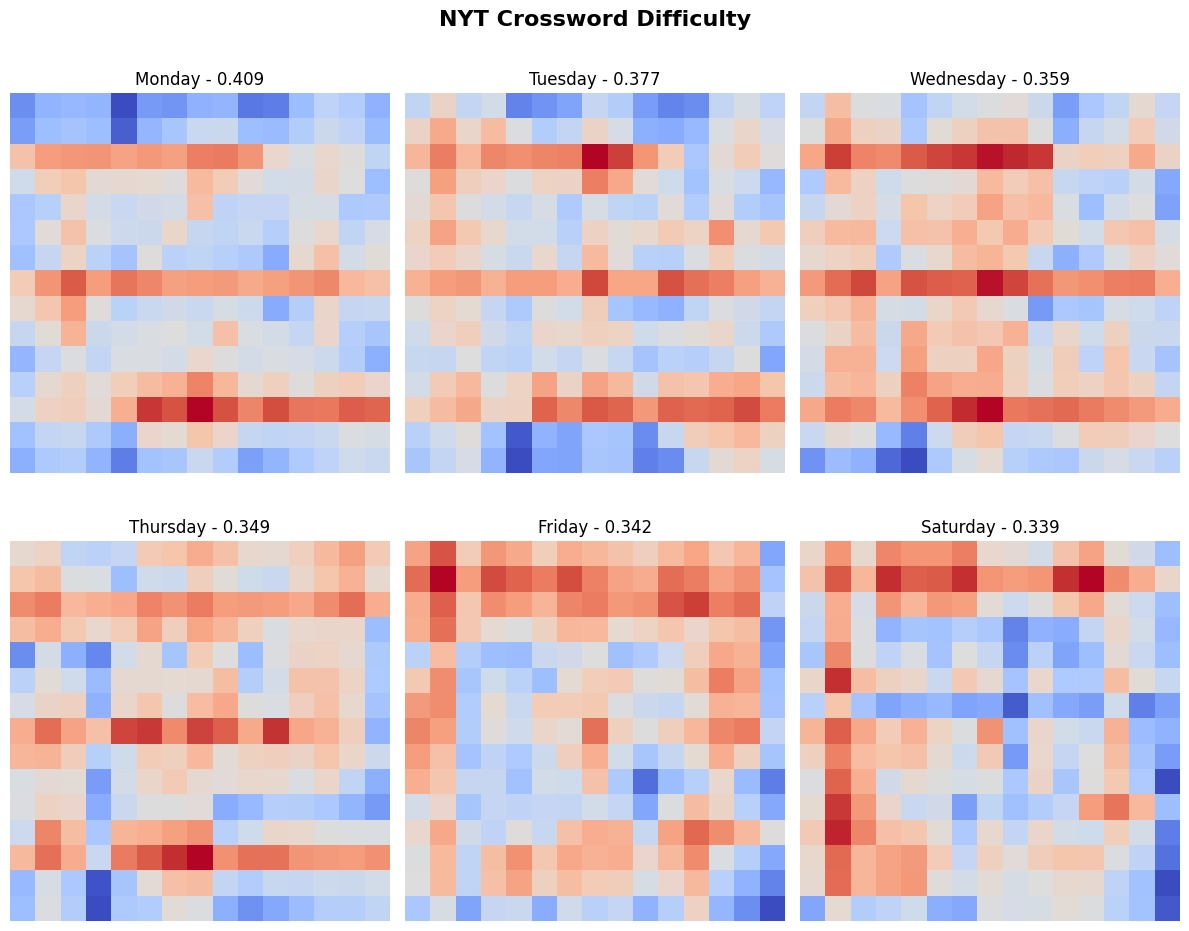

This I ran the embeddings for all clues in about 6000 puzzles and, according to our embedding heuristic, Friday is the hardest day of the week in the NYT.

| Day | Average Distance |

|---|---|

| Monday | 0.527 |

| Tuesday | 0.515 |

| Wednesday | 0.489 |

| Thursday | 0.497 |

| Friday | 0.478 |

| Saturday | 0.496 |

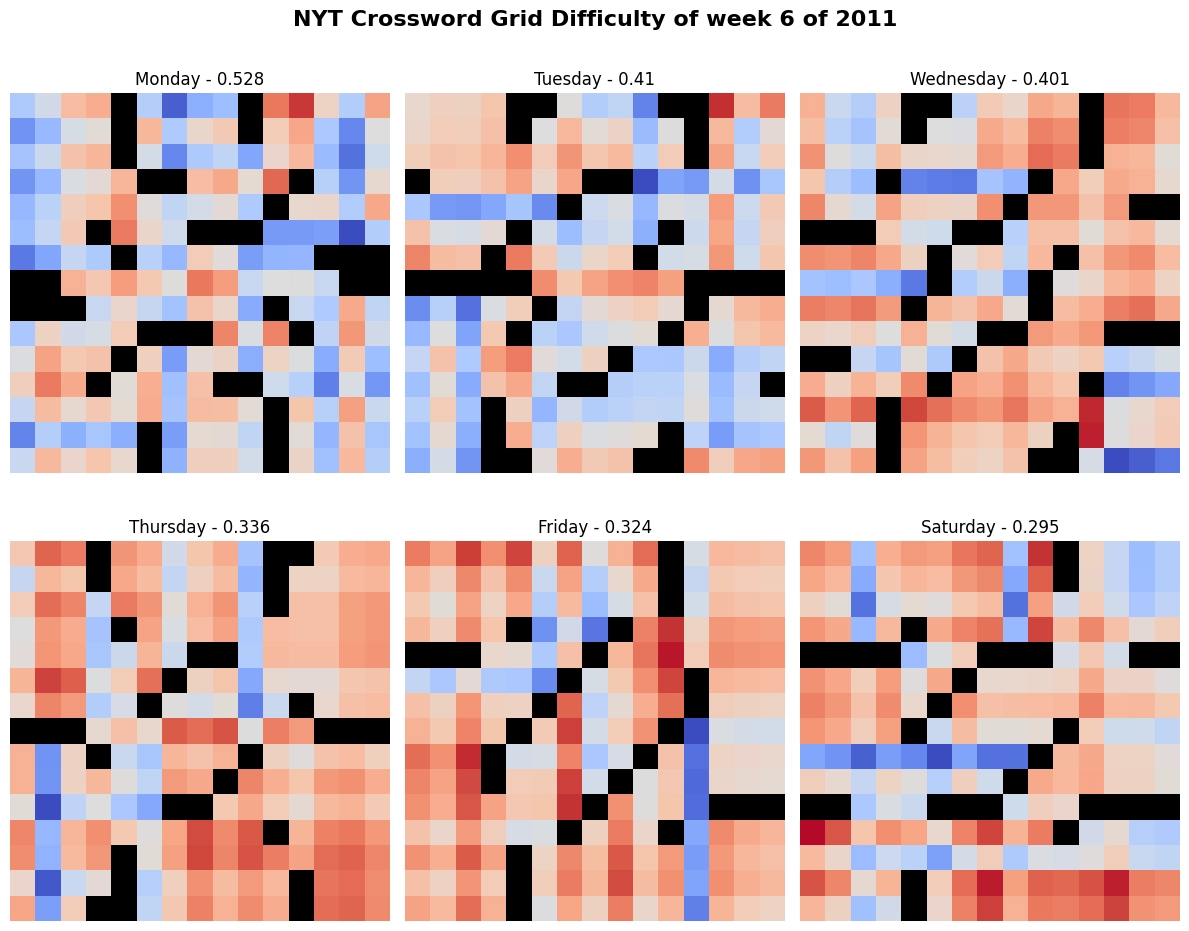

To visualise the progression in difficulty over the week, we can use colours to show the similarity on the grid, where red means less similar (harder to solve). As this diagram illustrates, difficulty increases over the week.

Here is the result of the same analysis, but carried out for all the puzzles in my dataset. And again, progression is apparent.

Can an LLM write a good Clue?

Writing clues is hard and that’s why editors - like Will Shortz of the NYT - exist. But what we do have, is a lot of data: words and their clues. By leveraging this dataset we can fine-tune an LLM to write the clues for us. In this case, we will use Llama-3 with 8B parameters, a model developed by Meta.

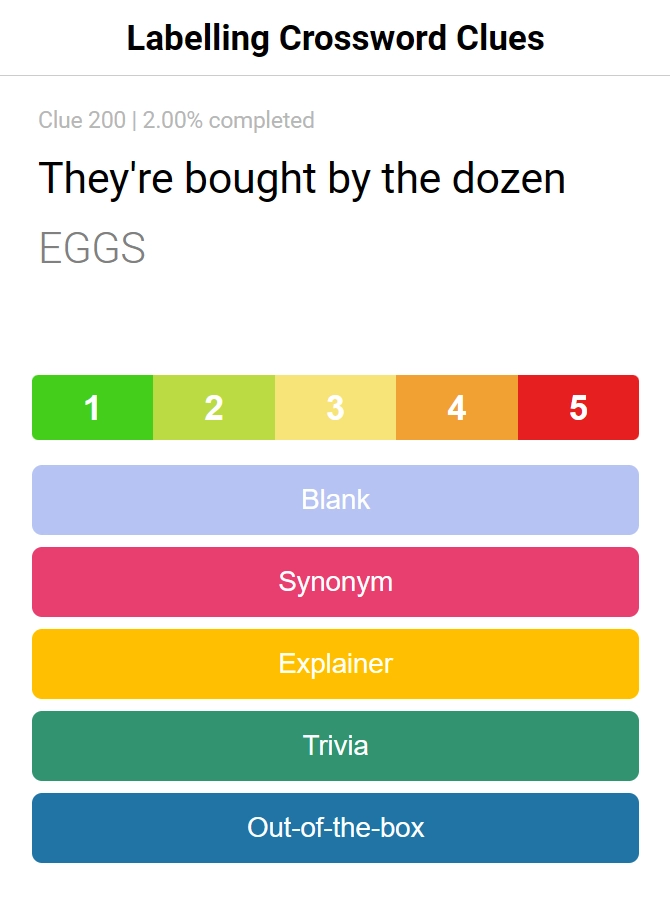

In order to have more control over the generated clues, I opted for labelling the clue data with more context. For about two hundred examples, I added tags: a difficulty rating (from 1 to 5) and a type of clue (blank, synonym, explainer, out-of-the-box, trivia ).

Some examples of labelled data:

{

"clue": "Roman author of \"Metamorphoses\"",

"word": "OVID",

"type": "trivia",

"difficulty": 4

},

{

"clue": "California's Big ___",

"word": "SUR",

"type": "blank",

"difficulty": 2

}

I used this Google Colab Notebook to fine-tune the LLM, adapted to my own dataset, to generate the following clues for the word “GADGET”.

| GADGET | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| blank | “___-whiz” | Telemarketer’s need | “Smart” phone feature | Astronaut’s radio, informally | Snoopy’s pet |

| synonym | Part of some new technology | A small portable electronic device | High-tech item | One way to access the Internet, informally | “Smart” person, in slang |

| explainer | Chew toy | Darn it, I’m out of | Electronic item that plugs into a wall | Laptop, in slang | Stereotypical science fiction item |

| trivia | One way to find a lost pet | Stereotypical British item | Maurice Micklewhite, Jr., Oscar winner | Tennis legend Arthur | Inventor’s need, briefly |

| out-of-the-box | What may be electronic but not digital? | Riddle, essentially | Gadget that may be paired | Something that can be played like a piano | Like an analog clock, but not quite |

As you can see the results are not very encouraging. Although there are some exceptions, for most instructions the model ignored the type and difficulty I asked it for.

Weirdly, Tennis legend Arthur came up quite frequently while testing, it might be some local minima that the model got stuck in while fine-tuning on trivia clues. I am really interested in getting this to work better, so if you have any ideas on how to improve this, let me know about it!

Putting it all together

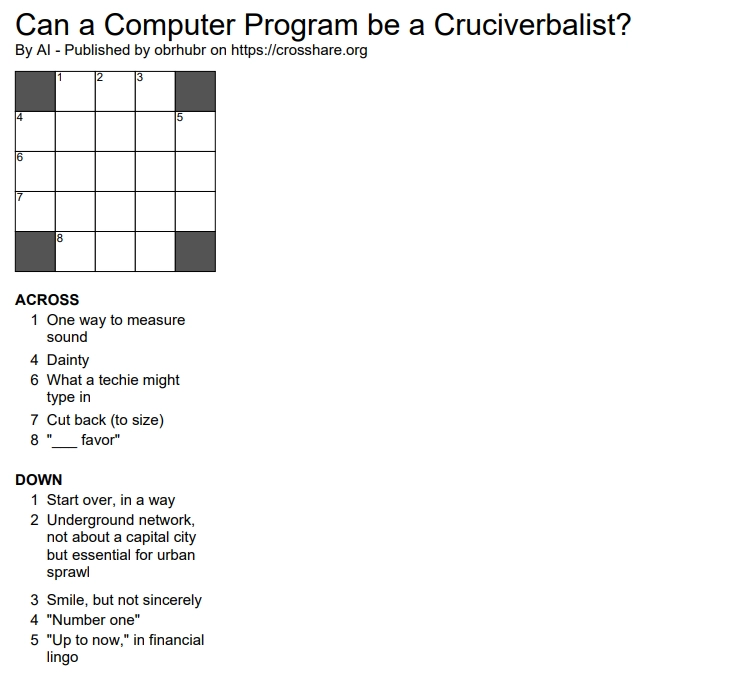

To finish off this article I wanted to put all elements together in order to create a final masterpiece: a fully computer generated crossword. You can play it here or print it out.