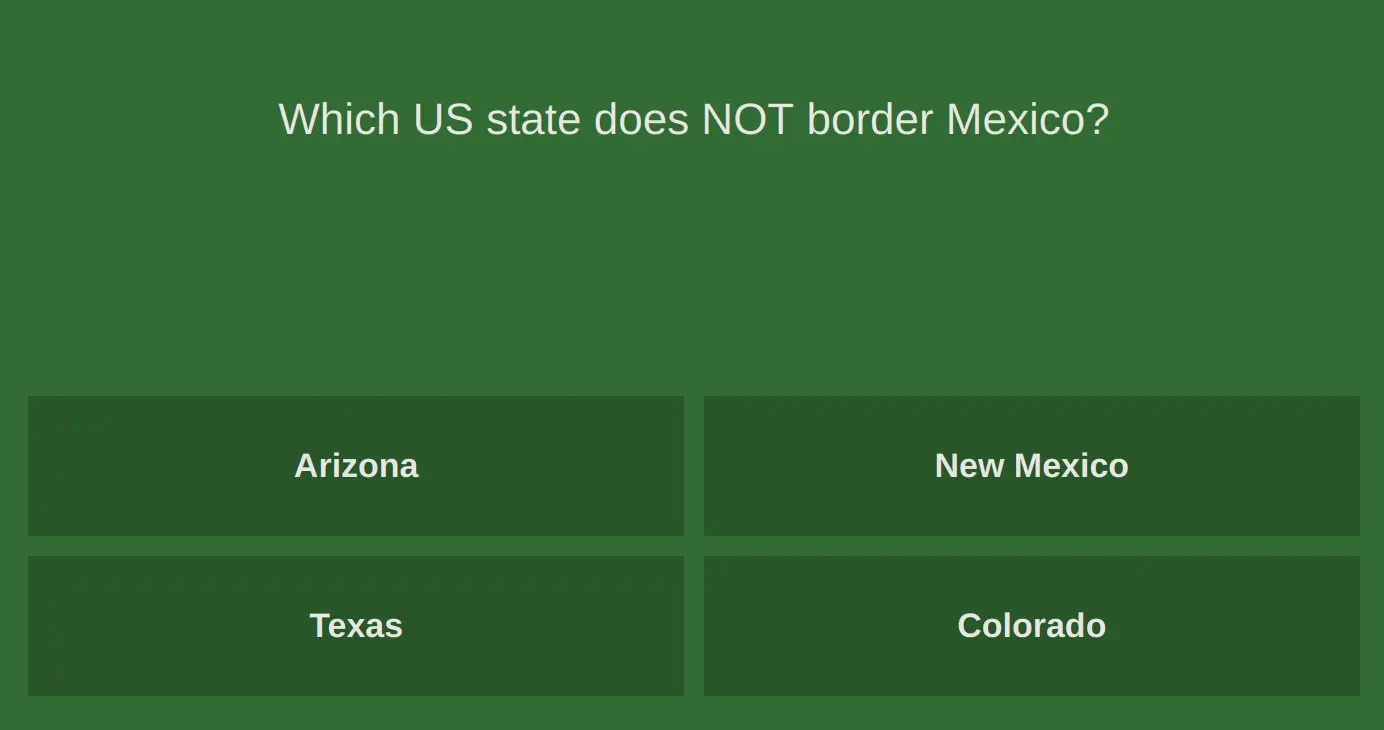

I’ve been playing the game Endless Quiz a lot with my friends recently, and one thing I’ve noticed is that you don’t need to know to be right. The game asks a question - which usually is about music, geography, physics, medicine, biology, computer science or the arts - and then presents four choices, always plausible.

So either you know the answer, by knowing the topic inside out, or you can guess. The same techniques and rules apply for a quiz with four choices and in the real world.

But you don’t need to learn about everything to be right about most things, just a few specific bits of knowledge can massively boost the amount of times you know the answer to difficult questions.

Heuristics

There are ways to guess that result in being right more often, these methods are called heuristics. You don’t just approach the problem from one angle, you find multiple related topics and engage with the question from as many sides as possible. You start out with things you know and try to figure out if they follow similar patterns. You could use etymology if possible, you could start with historical knowledge or geographical indications. A famous example which has influenced both pop-culture and bad job interview questions is the Fermi estimation.

The one thing that links all of these techniques is that you require some knowledge to start. You can’t Descartes yourself out of there, at some point, you have to set the tabula rasa. To get to a Fermi estimate of the number of tennis balls in a stadium, you have to know how large a tennis ball and a stadium are.

So the key to being right more often is to know more. Duh, you say, wouldn’t have needed to read the post to know that. But you can’t just go around learning things willy nilly, you have to be somewhat methodical, because what you learn is extremely important.

This post isn’t about the heuristics in particular, but rather about what to learn to be more efficient at jump starting a good heuristic.

What (and How) to Learn to Learn More

On the great beach of human knowledge, some bits of knowledge are seashells, some are grains of sand, and some just algae (Stay away kids, Oswald acted alone!). You want to pick the shells up first, then collect grains.

There are some obvious force multipliers when it comes to knowing more. Knowing how to read and use a computer are obvious things, but using spaced-repetition techniques like Anki can boost your recall feels like a hidden superpower in comparison.

Associating some bits of information with other, related bits is what helps to remember things better, in general. This is why mnemonic peg systems such as the major system, which associates words to numbers and helps memorise them (this is how some people know 100 digits of ). By using these techniques effectively, you’ll be able to learn more, faster.

Another fantastic force multiplier is language, specifically Greek and Latin words. This helps by giving you the ability to figure things out only through etymology. Let’s assume you didn’t know what agriculture meant. By knowing that it’s composed of ager (lat. for field) and cultura (lat. for cultivation) you could easily figure it out.

On another note, some mental math and basic statistics is always useful, one of my favourite blogs is Entropic Thoughts, I would especially recommend his posts about Bayes Rules, SPC and the Kelly Criterion. If you know how to square and take roots (don’t forget the logarithm) in your head, you’ll be able to apply more advanced techniques quicker.

What to Learn to Know More

Now that we know how to multiply the amount we can learn, we should focus on what to learn, because some knowledge can boost the amount of things you can correctly guess a lot more than others.

You should certainly know a lot of geography, the more the better. This is one of the most useful categories, as this can help for questions from history to politics, philosophy, etc… Know where countries are, how many there are, their flags and political systems. Know their rivers and what oceans or seas they border.

Biology and medicine are next, common suffixes and prefixes tell you a lot about the general topic, especially when it comes to nomenclature heavy fields like biology. An “-ose” is a sugar, an “-ase” is the enzyme acting on the root (lactase breaks down lactose for example). Know the parts of the brain and their function, about different organ systems and the body’s topology.

Don’t neglect history, the Greek and Roman times are a good foundation, major wars and conflicts around the world should also be familiar. US presidents and UK prime ministers or monarchs provide nice anchor points in history, which make modern periods easier.

You should also know painters, writers, musicians and their respective traditions. These helpfully usually also correspond to big historic shifts, which helps connect things. Philosophers and scientists (especially Greek ones) are also extremely useful.

Side effects

The biggest benefit of knowing more is that you start to notice more stuff: Sherlock Holmes notices Tobacco ash on the carpet, because he knows more than 140 types and varieties. If you know flags, you’ll notice flags: on buildings, people, cars and sticker-bombed toilet walls. That might not sound useful, but if it’s related to something you do want to know, it’ll sometimes prove to be key.

Noticing things isn’t always good, medical students have the problem of noticing too much, but I think the benefits outweigh the costs here.

My conclusion would be that specialisation isn’t bad (it certainly helps to be sure, which is mostly better than right), as long as it comes with a healthy dose of general knowledge. Knowing the rights things can increase the frequency of you being right by an enormous amount.

I don’t pretend to be an expert on this subject, and I would love for you to reach out and tell me if I have missed any techniques or areas that could help boost the efficiency of heuristics.